A topic that frequently confuses users in the #Node.js channel, is the Promise.try method provided by Bluebird. People often struggle to understand what it is, or why they should use it - and this isn't helped by the fact that almost all guides to Promises fail to demonstrate its use.

In this brief article, I hope to provide a better explanation of what Promise.try is, and why you should always use it, without exceptions. I'll be assuming that you already have some knowledge of Promises, and specifically about the role of .then.

Even if you are using a different Promises implementation (such as ES6 Promises), this article will still be useful to you - at the end of this article, I will explain how to achieve the same functionality without Bluebird.

So, what is it?

Simply put, Promise.try is like .then, without requiring a previous Promise. Now that's still a little vague, so let's start out with an example.

This is what some typical code using Promises might look like:

function getUsername(userId) {

return database.users.get({id: userId})

.then(function(user) {

return user.name;

});

}

So far, so good. We'll assume that database.users.get will return a Promise of some sort, and that that Promise will eventually resolve to an object with a name property.

Now, this is the same code, but using Promise.try:

var Promise = require("bluebird");

function getUsername(userId) {

return Promise.try(function() {

return database.users.get({id: userID});

}).then(function(user) {

return user.name;

});

}

As you can see, we've added Promise.try at the very start of the chain. Rather than chaining directly off database.users.get, we chain off Promise.try and simply return the result of database.users.get, like we would normally do from a .then.

So... what is all this good for?

The above may look like needless extra code. But in practice, there are several advantages:

- Better error handling; synchronous errors are propagated as rejections, no matter where in the process they occur.

- Better interoperability; no matter what Promises implementation the third-party method uses, you will always be working with your preferred implementation.

- Easier to 'scan'; all code is horizontally at the same indentation level, so it's easier to see what's going on at a glance.

Below, I'll address each of these points individually.

1. Better error handling

One of the touted benefits of Promises is that we can treat synchronous and asynchronous errors in the same way - synchronous errors are simply caught, and 'repropagated' as a rejected Promise. But is this really the case? Let's have a look at a slightly modified version of our first example:

function getUsername(userId) {

return database.users.get({id: userId})

.then(function(user) {

return uesr.name;

});

}

In this modified version, we've mistyped user.name, so that it now says uesr.name. This would normally fail, as uesr is undefined, and so can't have any properties. Indeed, this will be caught within the .then and turn into a rejected Promise, as we expect.

But what if database.users.get throws synchronously? What if there's a typo or other error in the third-party database code, which we didn't write? The error-catching feature of Promises works by virtue of all your synchronous code being in a .then, so that it can wrap it in a giant try/catch block.

But... our database.users.get isn't in a .then block! The Promises implementation thus doesn't have access to that chunk of code, and can't wrap it. Our synchronous error will remain a synchronous error, and now we're back where we started - having to deal with two kinds of errors, synchronous and asynchronous.

Now, let's look back at our example using Promise.try again:

var Promise = require("bluebird");

function getUsername(userId) {

return Promise.try(function() {

return database.users.get({id: userID});

}).then(function(user) {

return user.name;

});

}

I said before that Promise.try is like a .then, but without requiring a previous Promise. That holds true here, as well - it will catch the synchronous error in database.users.get, just like a .then would have!

By using Promise.try, we've streamlined our error handling to cover all of the synchronous errors, not just those after the first asynchronous operation (as that is where our first real .then callback would otherwise be).

Interjection: Promises/A+

Before we move on to the next point, let's cover what Promises/A+ is, and what role it plays in the ecosystem. The Promises/A+ site summarizes it as follows:

An open standard for sound, interoperable JavaScript promises—by implementers, for implementers.

Put differently, it's a way to ensure that different Promises implementations (Bluebird, ES6, Q, RSVP, ...) work together flawlessly, out of the box. This Promises/A+ specification is why you can use pretty much any Promises implementation you prefer, and why you don't have to care about which implementation a third-party library (like, for example, Knex) uses.

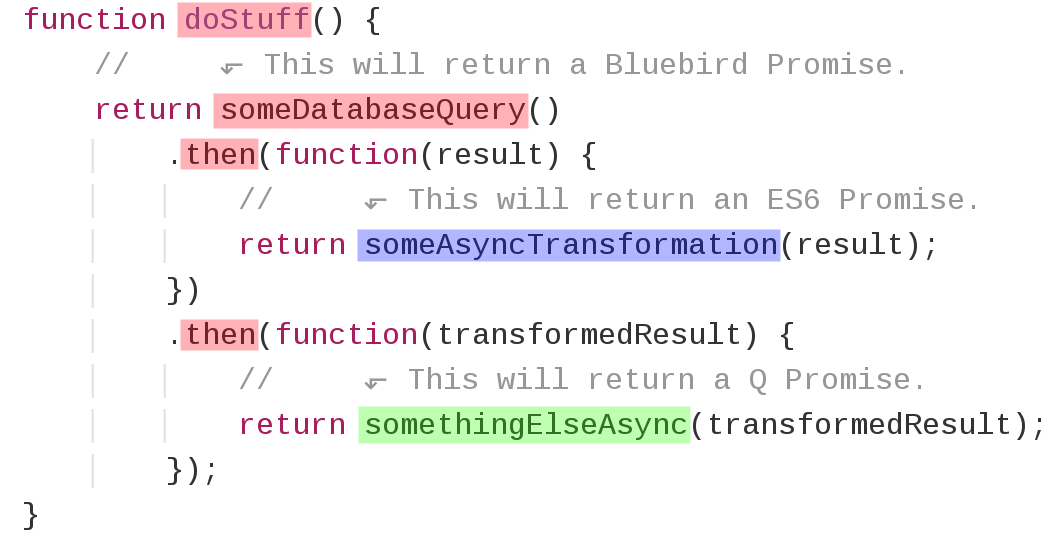

To illustrate what Promises/A+ does for you as a user:

All the functions highlighted in red return Bluebird Promises, the one in blue returns an ES6 Promise, and the one in green returns a Q Promise.

Note how even though we are returning an ES6 Promise from the first callback, the .then that wraps it will still return a Bluebird Promise. Similarly, even though the second callback returns a Q Promise, our doStuff method will still return a Bluebird Promise.

This happens because, aside from catching synchronous errors, .then will also wrap the return values and ensure that they end up being a Promise from the same implementation that the .then itself comes from. In practice, this means that the first Promise in the chain determines what implementation you will be working with.

This is a practical way to ensure that you are always working with a predictable API. The only Promises implementation you have to care about, is whatever the first function in the chain uses - no matter what comes afterwards.

2. Better interoperability

The above isn't always desirable, however - for example, look at this example:

var Promise = require("bluebird");

function getAllUsernames() {

// ⬐ This will return an ES6 Promise.

return database.users.getAll()

.map(function(user) {

return user.name;

});

}

If you are not familiar with map and you'd like to know more, you can read this article.

The .map feature we are using in this particular example is a Bluebird feature, and is not available on ES6 Promises. We can't use it here, even if we are using Bluebird in our project otherwise - simply because the first function in the chain (database.users.getAll) returned an ES6 Promise rather than a Bluebird Promise.

Now, let's look at the same example again, but this time using Promise.try:

var Promise = require("bluebird");

function getAllUsernames() {

// ⬐ This will return a Bluebird Promise.

return Promise.try(function() {

// ⬐ This will return an ES6 Promise.

return database.users.getAll();

}).map(function(user) {

return user.name;

});

}

Now we can use .map! Because we are starting with Promise.try, which originates from Bluebird, all our subsequent Promises will also be Bluebird Promises, no matter what happens in the .then callbacks.

By using Promise.try like this, you can decide for yourself what implementation you want to be working with, by ensuring that the first Promise in the chain comes from your preferred implementation. You can't do this with .then, because that'd require you to chain off some other Promise - which would defeat the point.

3. Easier to scan

The final benefit is one of readability. By starting every chain with Promise.try, all the actual 'business logic' exists within a callback at the same (horizontal) level of indentation. While this might seem like a minor benefit, it actually makes a fairly significant difference, due to how humans scan large amounts of text.

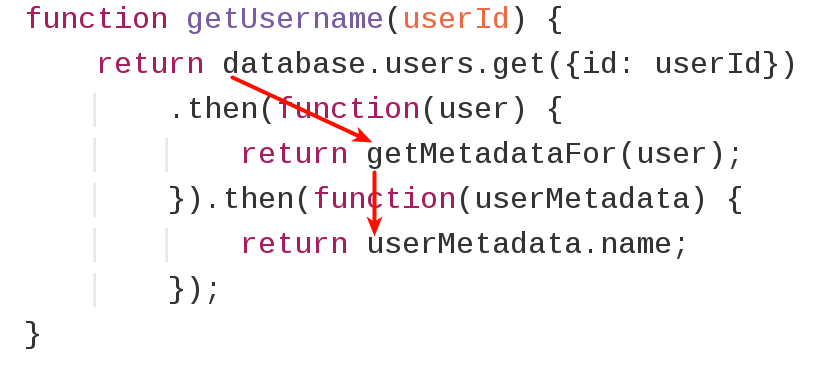

To illustrate the difference, this is how you would visually scan the code without Promise.try, using a common indentation style:

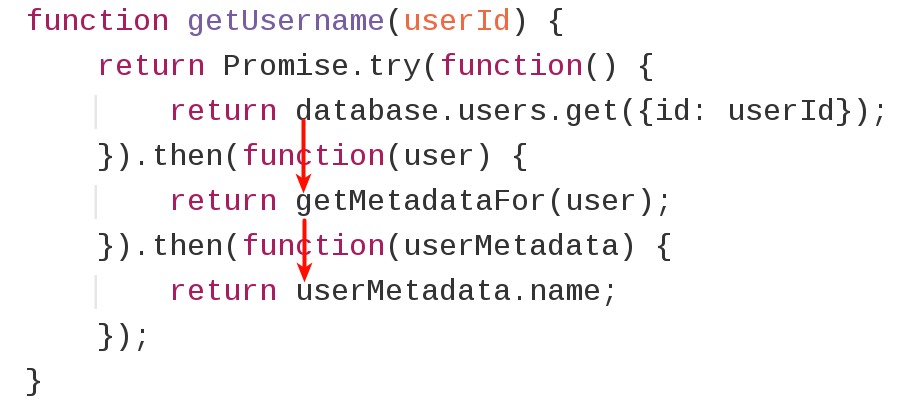

... and the same code, but using Promise.try:

Even though the code looks slightly 'noisier', it's still easier to get a quick impression of the code, simply because your eyes have to 'seek' less.

What if I'm not using Bluebird?

To my knowledge, Bluebird is currently the only Promises implementation that ships with Promise.try out of the box. However, it's relatively easy to replicate the functionality in other implementations, as long as their version of new Promise catches synchronous errors.

For example, es6-promise-try is an implementation that I've written for ES6 Promises, and it works in the browser too. I have not gotten around to writing its documentation yet, but it works in essentially the same way as Promise.try - however, instead you call promiseTry like below:

var promiseTry = require("es6-promise-try");

function getUsername(userId) {

return promiseTry(function() {

return database.users.get({id: userID});

}).then(function(user) {

return user.name;

});

}

Keep in mind that es6-promise-try will assume that your environment supports ES6 Promises - if that is not the case, you'll want to use something like es6-promise as a polyfill.

I'd seriously recommend looking at Bluebird instead, though, as it has much more robust error handling and debugging features. Usually, ES6 Promises are only the ideal option in constrained environments like old versions of Internet Explorer, or when trying to the reduce bundle size of frontend code.

If you know of Promise.try implementations for other Promises implementation, then please let me know, and I'll add them here! My contact details are at the bottom of this page.

I am currently offering Node.js code review and tutoring services, at affordable rates. More details can be found here.

1G4JG9oFPmpwzEmSH4gnLCdE8hBprdJuDG

1G4JG9oFPmpwzEmSH4gnLCdE8hBprdJuDG